Patagonia’s ‘Dirtbag’ Billionaire Is Out to Transform Philanthropy

David Gelles’s new book examines the life of Yvon Chouinard, whose $3 billion outdoor recreation company is now giving its profits to a charity fighting the environmental crisis.

September 9, 2025 | Read Time: 6 minutes

“Hopefully this will influence a new form of capitalism that doesn’t end up with a few rich people and a bunch of poor people.”

That’s what Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, said in September 2022 when he announced his decision to give away his company. His plan was unusual, some say even revolutionary. Instead of selling the $3 billion outdoor clothing and equipment company to the highest bidder, going public, or leaving it to family, Chouinard and his wife, Malinda, transferred 100 percent of the company’s voting stock to a specially designed trust and a 501(c)(4) social welfare nonprofit called the Holdfast Collective to fund the fight against climate change and protect nature.

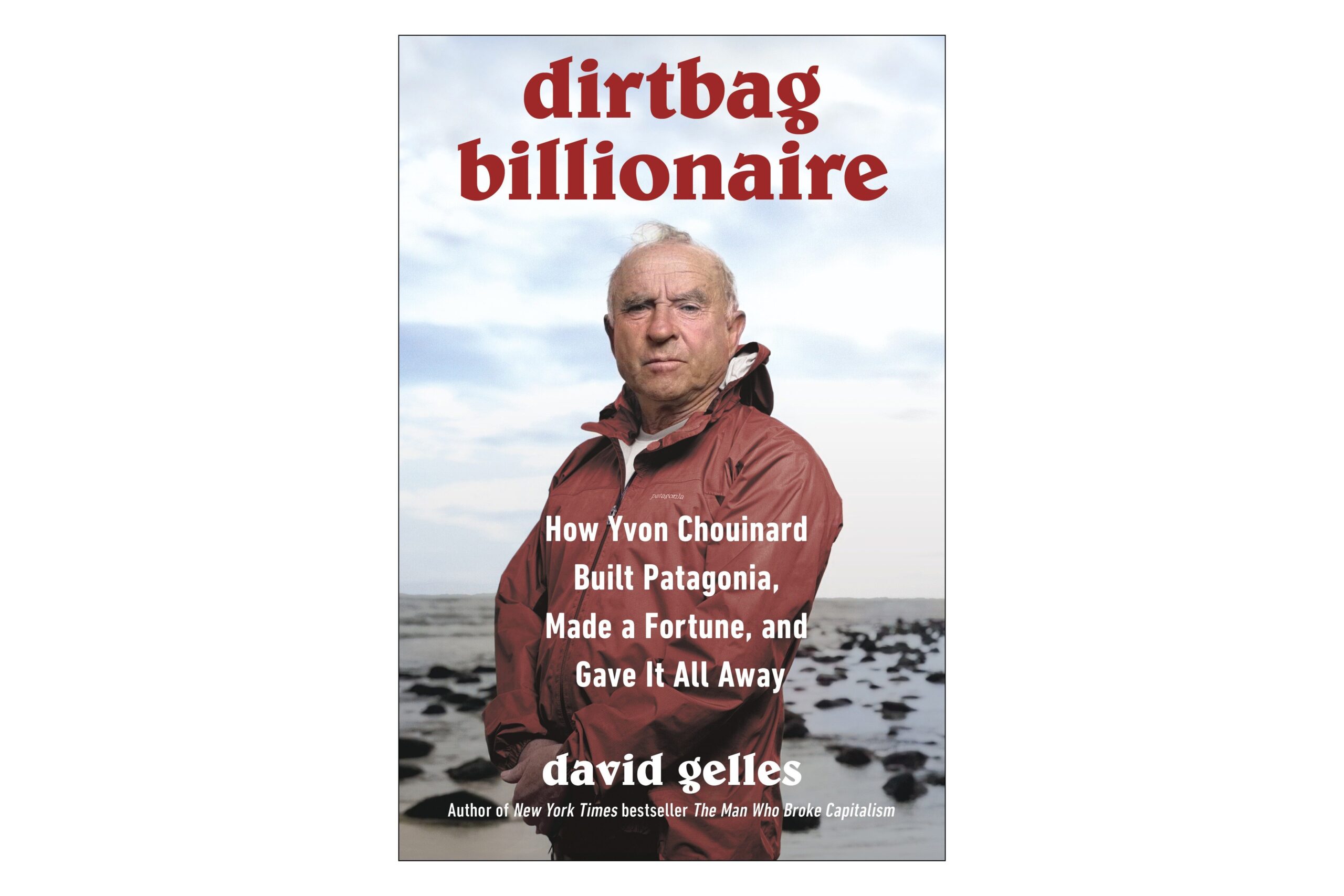

Who does that? That’s the question New York Times climate reporter David Gelles sets out to answer in his latest book Dirtbag Billonaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away. Gelles takes the reader down a zigzagging trail from Chouinard’s upbringing in rural Maine and southern California to his formative days as a “dirtbag climber” — a term, Gelles explains, “affectionately bestowed on poor, itinerant outdoorsmen so uninterested in material possessions they are happy to sleep in the dirt” — to his somewhat accidental founding of Patagonia to support his moderately profitable climbing equipment business, which Chouinard in turn had started to fund his obsessive climbing habit.

Go Deeper

-

Corporate Responsibility

Why Patagonia’s Purpose-Driven Business Model Is Unlikely to Spread

In Gelles’s hands, Chouinard keeps morphing. He is a rough outdoorsman and then a small businessman determined to make climbing tools with low-to-no environmental impact and then the founder of a booming business opposed to consumerism, environmental degradation, and the norms of corporate capitalism.

The nonprofit story is just as eye-popping. Since the late 1990s, Patagonia has given away about $1 million a year in unrestricted funding to environmental nonprofits. In 2002, Chouinard and his colleagues launched 1% for the Planet, which has since spurred over $800 million from more than 4,500 businesses to support environmental partners around the globe. And in its first year of operation, the Holdfast Collective has made 690 grants and commitments totaling more than $61 million. In total, those funds have helped protect 162,710 acres of wilderness around the world, Gelles reports. The Chronicle interviewed Gelles about this philanthropy-first capitalist, his colleagues and family members, and their efforts.

You mention toward the end of your book that Michael Bloomberg has followed Yvon Chouinard’s lead in deciding to give the vast majority of his $22.5 billion company to his Bloomberg Philanthropies, and there is the example of David Green, the founder and CEO of Hobby Lobby, and his multi-billion pledge to Christian philanthropy. Why are there so few examples of philanthropy-first companies at a time when there are so many billion-dollar enterprises?

There are a handful of other well-known companies with strong charitable legacies. Hershey, Lego, and Rolex all come to mind. But because most big corporations are publicly traded, the expectation is that most of their profits are returned to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividends, not spent on charitable causes.

That’s what makes Patagonia so unique. Yvon Chouinard never took on any outside investors and never took the company public. As a result, he was able to funnel a fair bit of the company’s profits and personal wealth toward conservation and environmental activism for the decades that he owned the company. And then in 2022, he and his family — who still controlled all the shares — were able to give the company away and set up a structure that ensures all future profits go to those causes as well.

Do you expect we’ll see a significant rise in B Corps and public benefit corporations? Or do you think the numbers will remain small and most big companies will continue to donate through their foundations and employee charity matching programs?

I think it’s fair to call it a small but growing movement. There are thousands and thousands of companies out there, and for now at least, only a tiny minority are going to pursue real charitable initiatives. It’s also important to note that just because a company is a B Corp or a public benefit corporation, that doesn’t mean that they’re automatically giving away most of their profits. All that said, I do believe that especially among entrepreneurs and founders these days, there is more and more of an appetite to run businesses in a way that is good for their people, good for the planet, and good for society at large. And Patagonia is proof positive of that.

The Conservation Alliance, the Textile Exchange, 1% for the Planet, the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, the B Corp movement, and Time to Vote — how is it that Chouinard and his colleagues made time for so many noncommercial interests? And how much have those interests helped sell the Patagonia brand?

One of the surprising things about reporting this book was finding Patagonia’s fingerprints all over the corporate world. You mentioned those groups, but there are many other official and unofficial ways in which the company made its imprint on a variety of industries, including apparel, manufacturing, and food. It wasn’t really an issue of time management for the team — they were promoting these causes and trying to get other companies on board because they believed it was the right thing to do. And it certainly wasn’t to enhance the brand. Patagonia has a very conflicted relationship with media and marketing.

In writing the book, you seem to have spent considerable time with Chouinard, his wife Malinda, and their children, Fletcher and Claire. How did they avoid the public battles typical of families with billions in assets? And why was setting up a private foundation or giving the reins to his kids something Chouinard decided not to do?

I asked Chouinard this very question and he told me: “I raised them right.”

Chouinard was never enamored with money or material possessions, and his children never got the taste for riches, either. To be clear, they’re all living comfortable lives. They own their homes, travel when they want, and I’m sure Chouinard’s grandchildren won’t have to worry about paying for college.

But the passions that enraptured Chouinard himself — being in nature, participating in sports, protecting the natural world — are the same things that motivate his wife and two children. As for why they didn’t set up a foundation, it really had to do with their intense desire for privacy. They quite simply didn’t want anything with their name on it — not a building, not a school, not an endowed chair, and not a foundation.

Has Patagonia changed its commitments to diversity, equity, and inclusion or environmental justice in reaction to the Trump administration’s opposition to these efforts?

No. Patagonia is one of the few companies out there that is still speaking out loudly about what it sees as this administration’s rising authoritarianism and efforts to make America less healthy, less safe, and ultimately less abundant.